I seem to have developed an obsession of sorts with China. It started many years ago when I read Crashed by Adam Tooze, though that interest eventually waned. It flared up again sometime in August 2024 when my colleagues and I started a daily finance podcast and a newsletter at work.

A few months in, I was writing more stories about the Chinese economy than on any other topic—so much so that I became the butt of my colleagues’ jokes. For a minute, it really did seem like it was a podcast exclusively about the Chinese economy. In my defense, I couldn’t help it because China was constantly in the news and there were monumental shifts afoot in the country.

Since then, I've been learning more about China and its economy. At this point, one thing seems clear to me: it is impossible to understand the world—or even the global economy—without an understanding of China. Another realization from my relatively short learning journey is that most mainstream narratives about China are not only wrong but also dangerous and misguided (more on that later).

But to take a step back, you might ask: why even bother with China, and why should you learn more?

It’s a fair question—especially if you don’t live in China. Let me share a few numbers that illustrate why China matters:

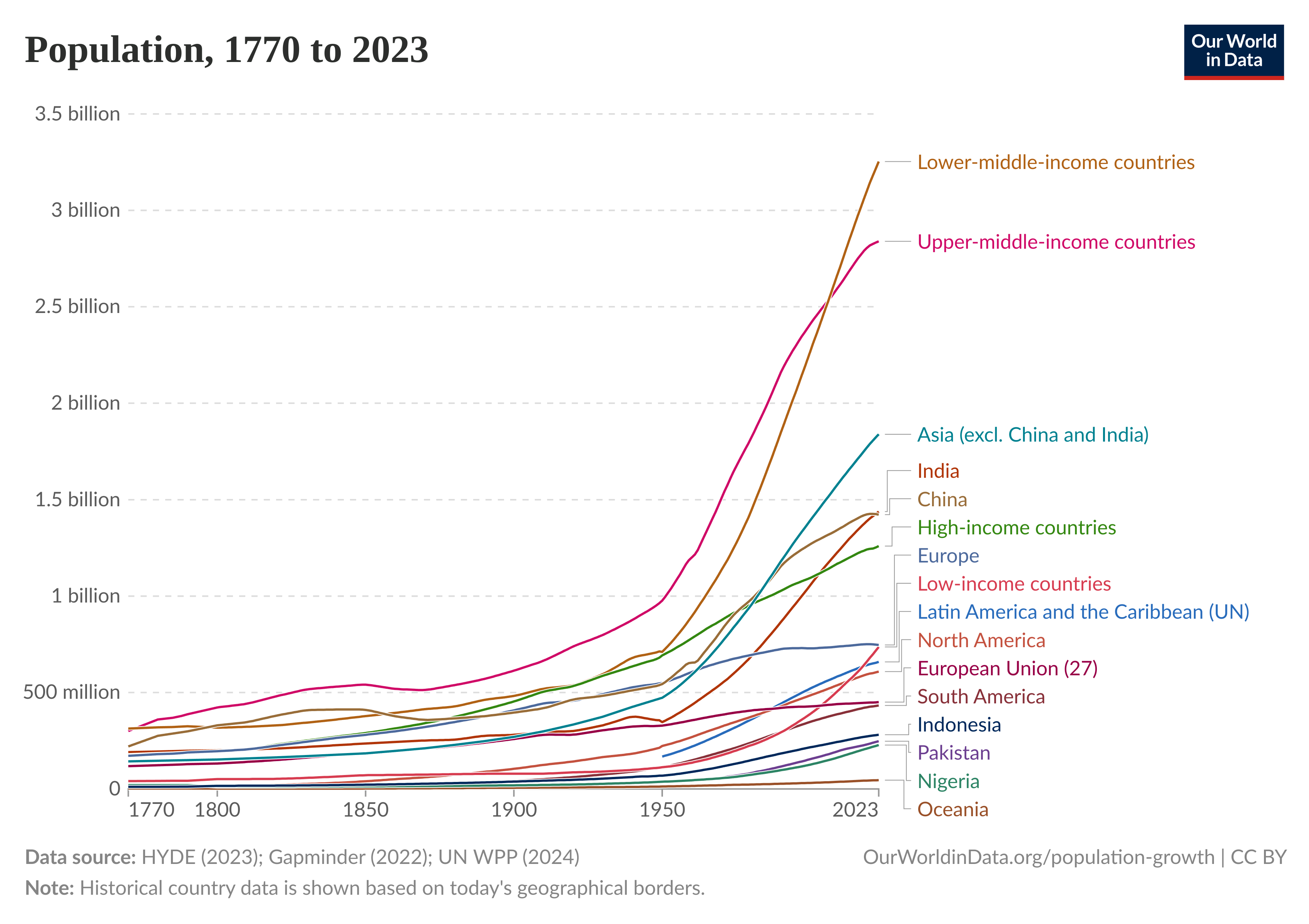

Population

At 1.4 billion, its population is almost as large as India’s (barring a few decimals). So, what China does matters to the rest of the world.

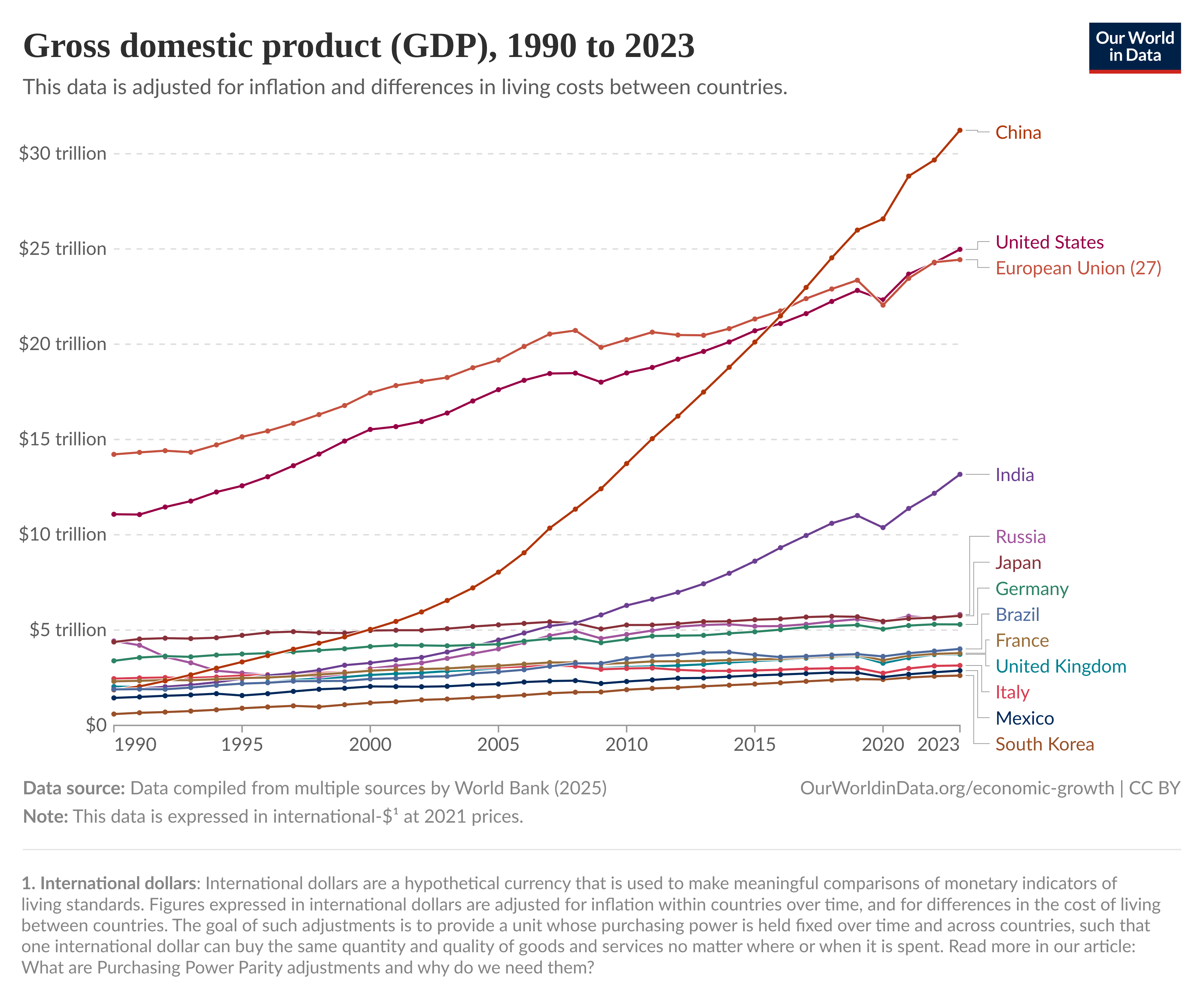

Economy

China is the world’s second-largest economy by nominal GDP 3. However, when measured by purchasing power parity (PPP), China’s economic stature is even more impressive.

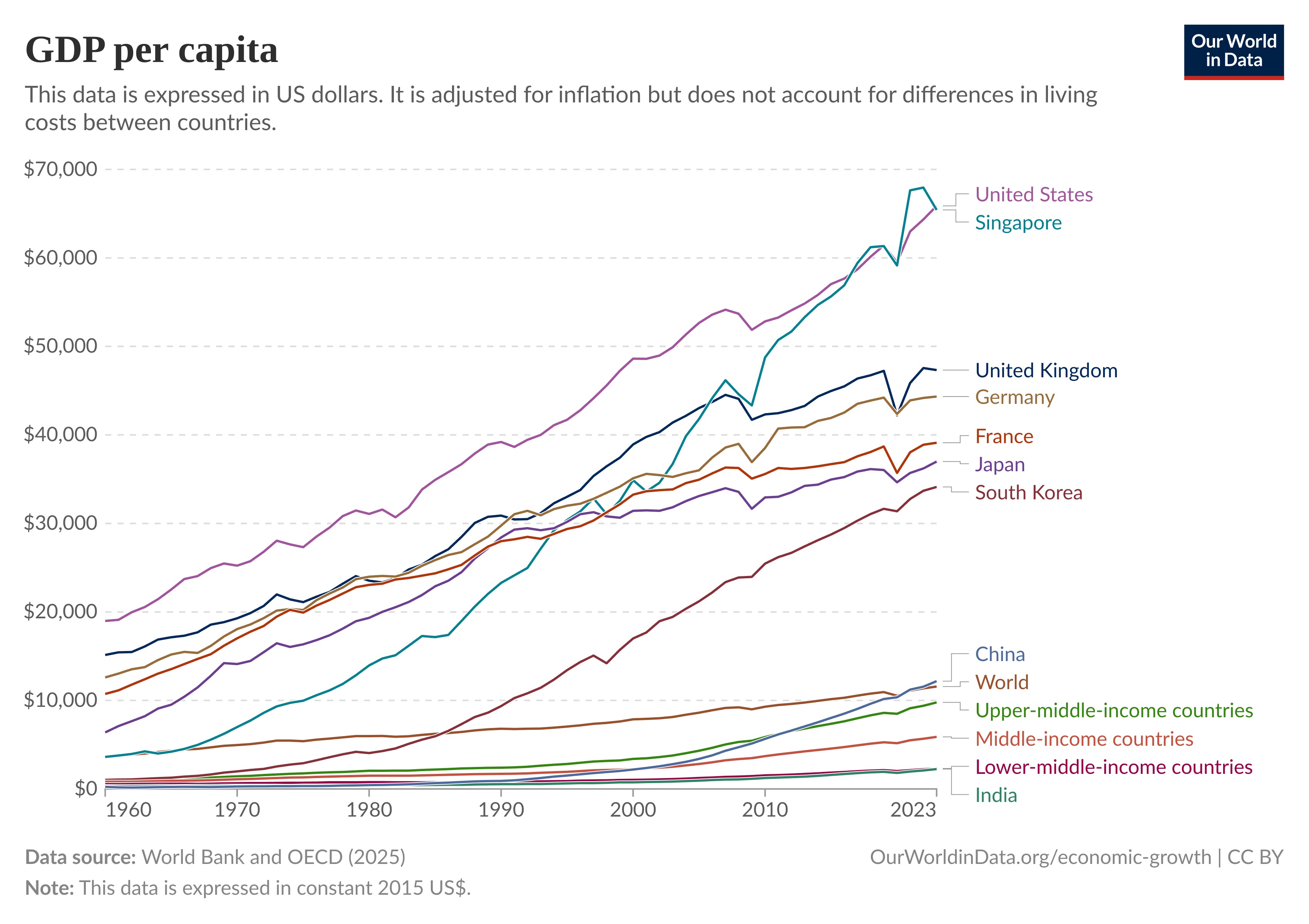

While its GDP per capita remains much smaller, China has made remarkable progress.

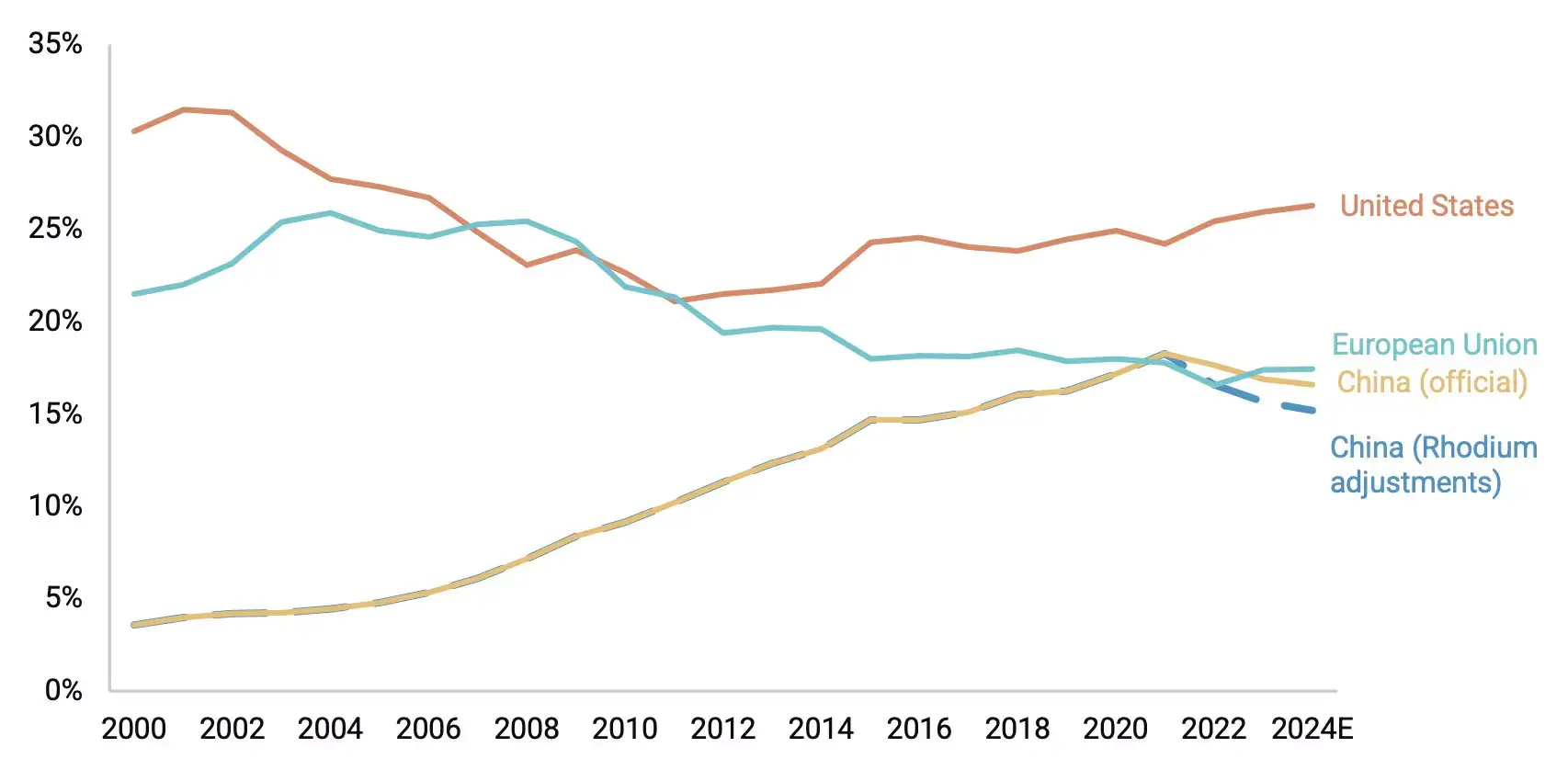

What's stunning is the rate at which China has grown. China accounted for about 4% of world GDP in 2001, but as of 2023, its share was about 17%.

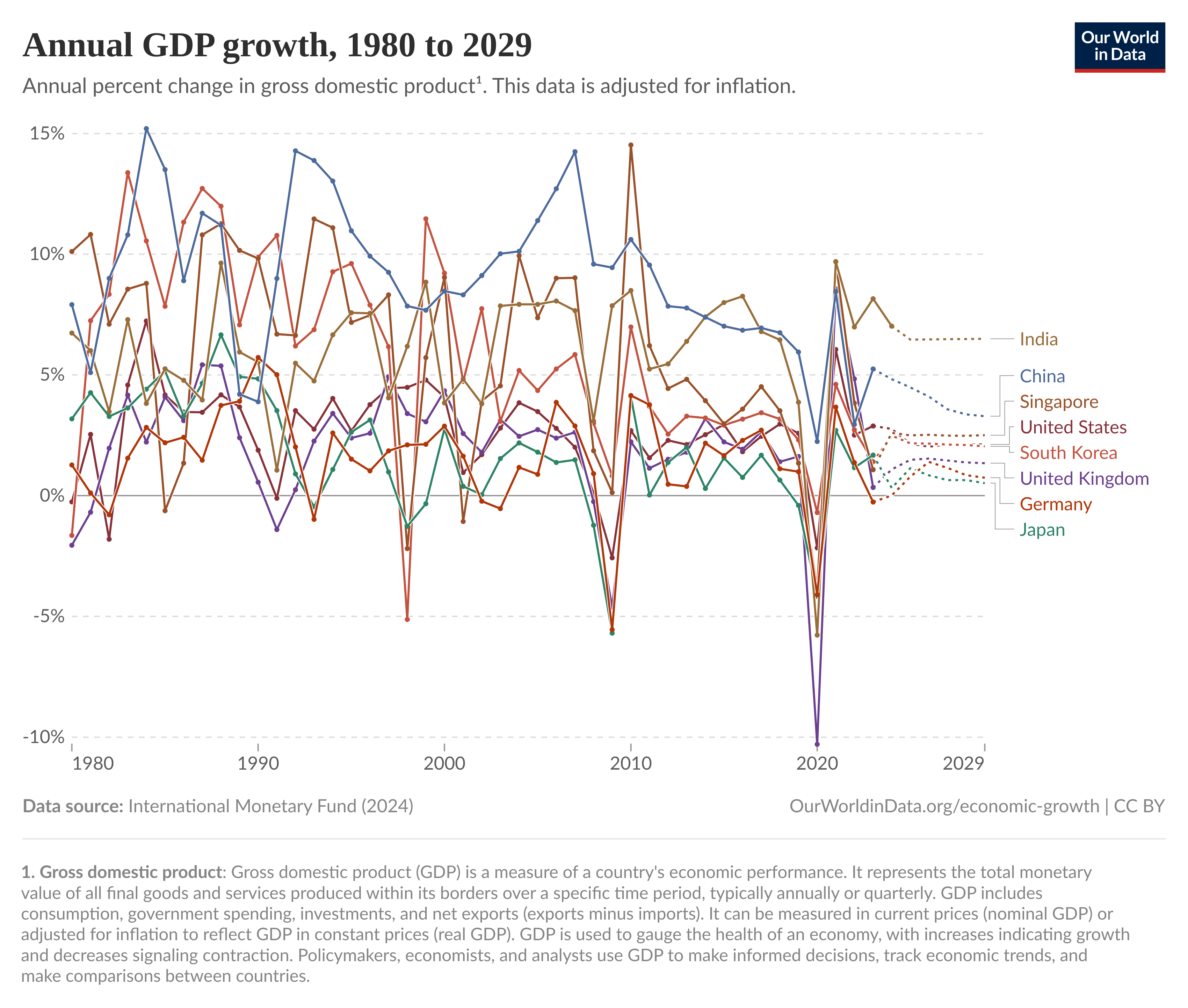

From 1989 until 2024, Chinese GDP averaged about 8.81%, and its economy roughly doubled every eight years. That’s a stunning rate of growth for a country of China’s size.

What happens when you grow at such spectacular rates?

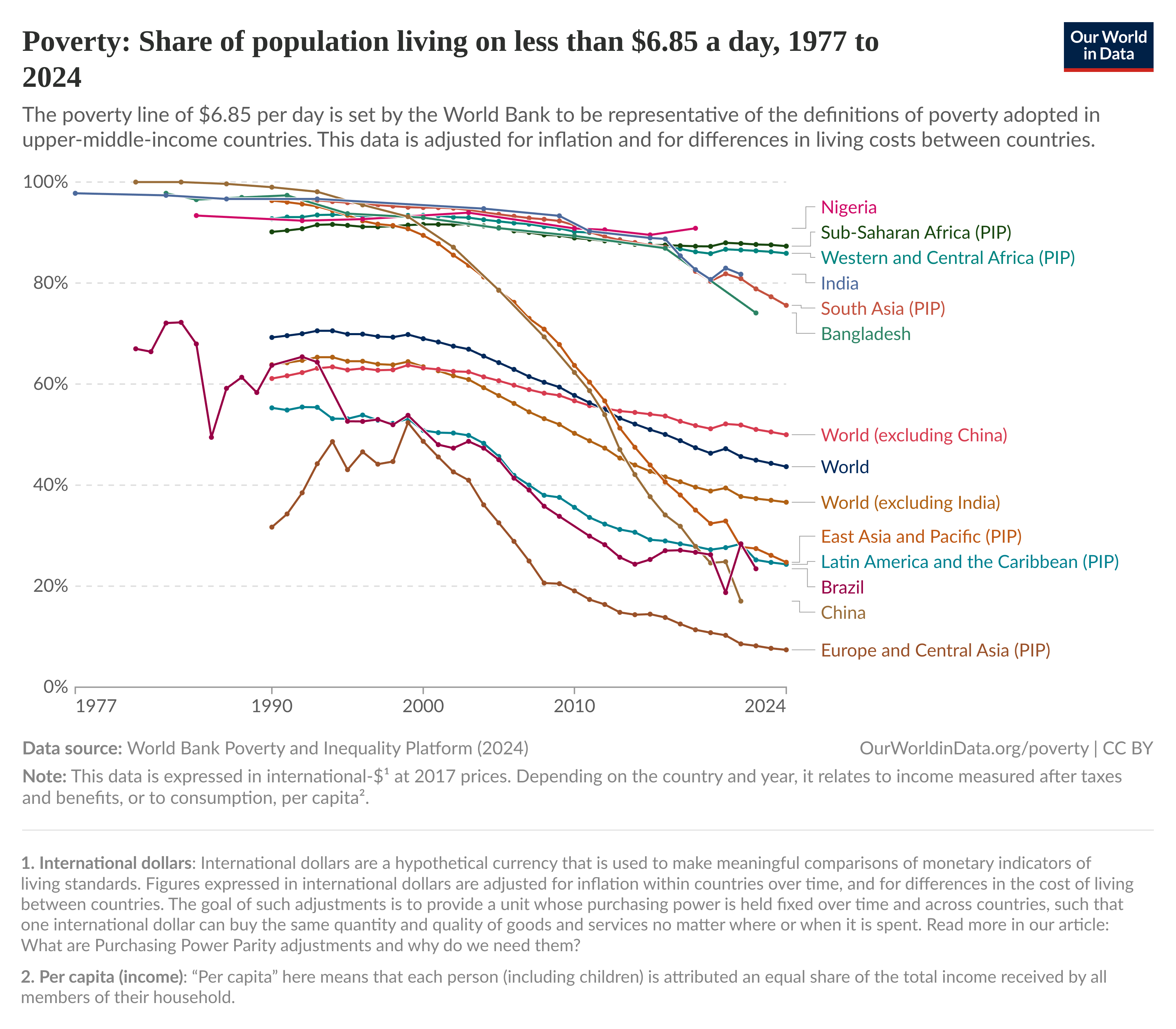

China has lifted close to a billion people out of absolute poverty. In 1977, virtually 100% of the population lived on less than $6.85 a day. As of 2024, that percentage had dropped to just 17%. Another perspective: in 1981, 97% of people in the Chinese countryside and 70% in cities lived on less than $2.15 a day—the threshold for extreme poverty. By 2020, the share of Chinese people living in extreme poverty was below 1%.

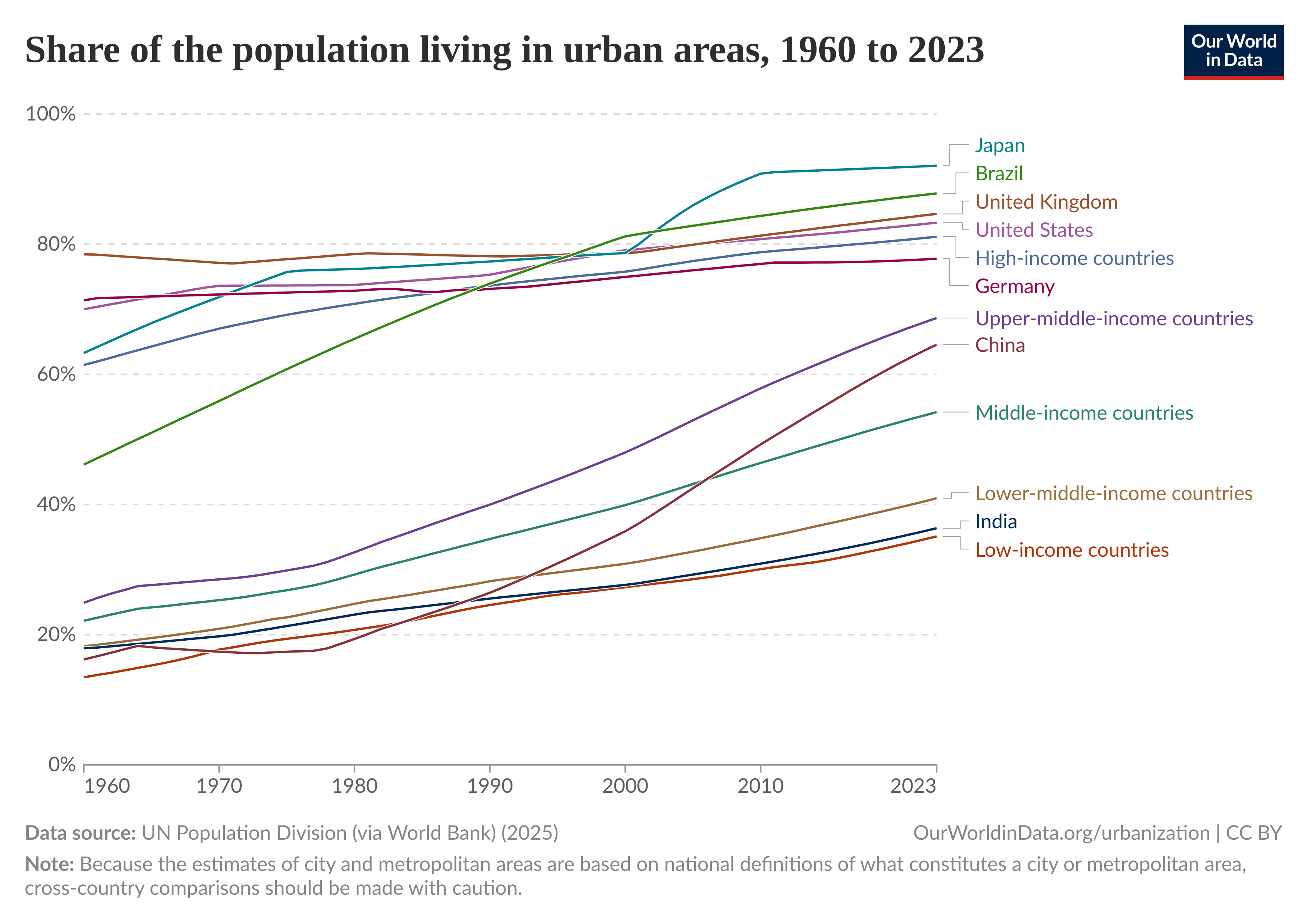

What happens when you nearly eradicate extreme poverty? Massive urbanization follows. In 1960, only 16% of Chinese citizens lived in urban areas; by 2023, that figure had risen to 65%. Imagine the amount of infrastructure, industrial bases, housing, power generation facilities, schools, hospitals, and more that had to be constructed to accommodate this gigantic shift in a country of over a billion people.

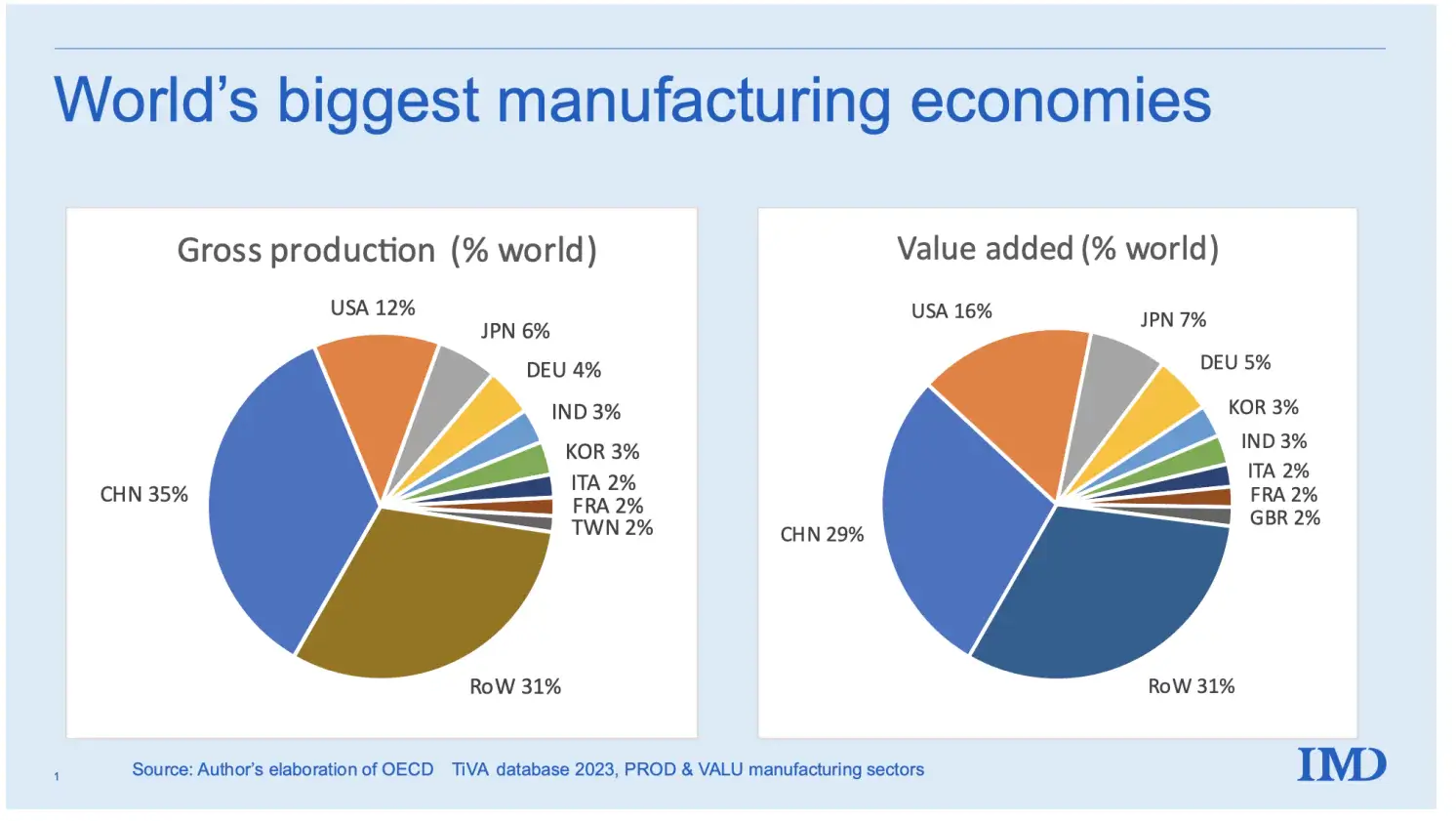

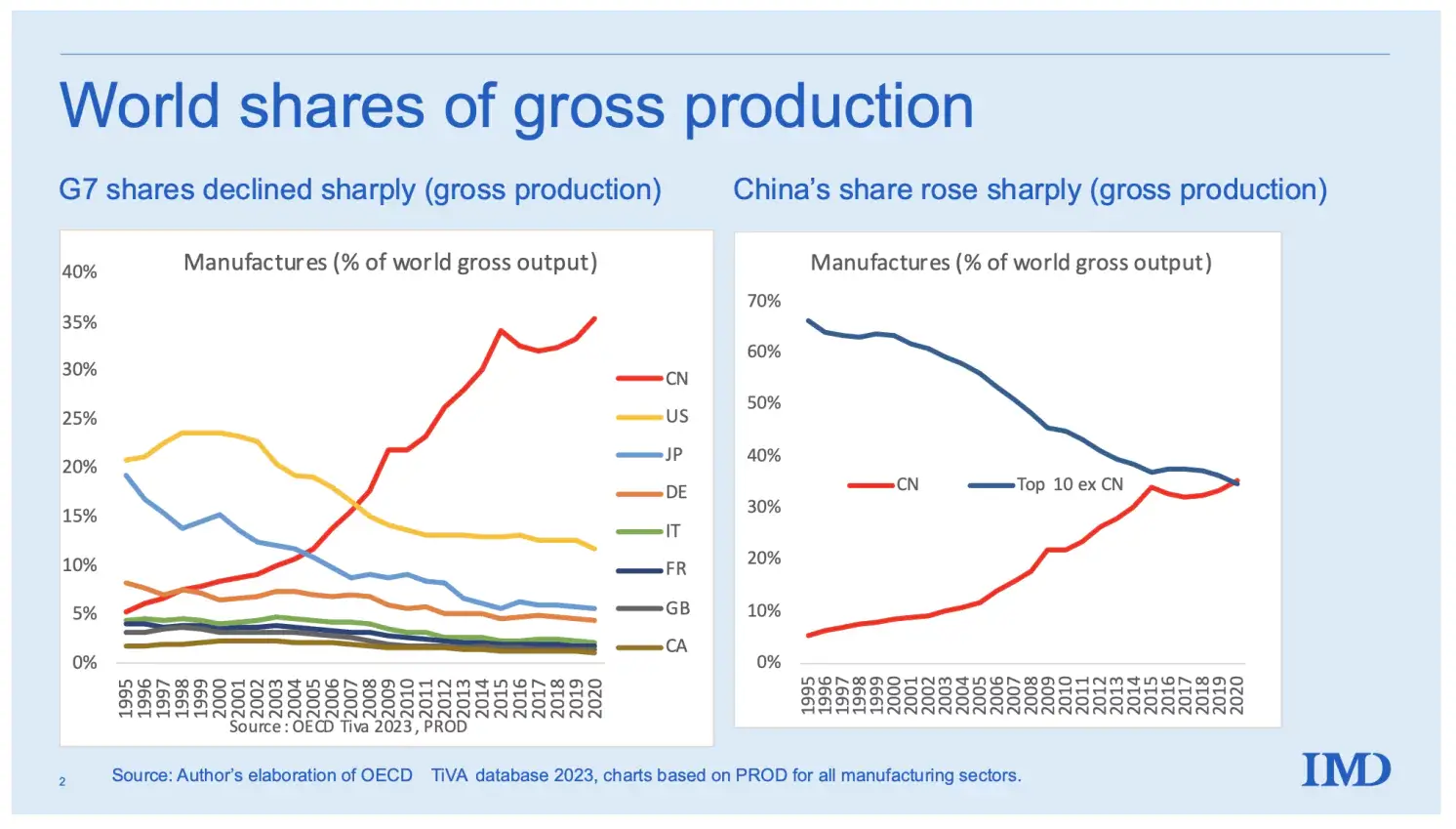

In 2001, China accounted for about 9% of global gross manufacturing and 7% of manufacturing value added. By 2020, these figures had risen to 35% and 29%, respectively. In 1995, China accounted for barely 3% of world manufacturing exports, and as of 2020, that share had grown to 20%. To put the scale into perspective, China manufactures more than the next ten largest manufacturing nations combined.

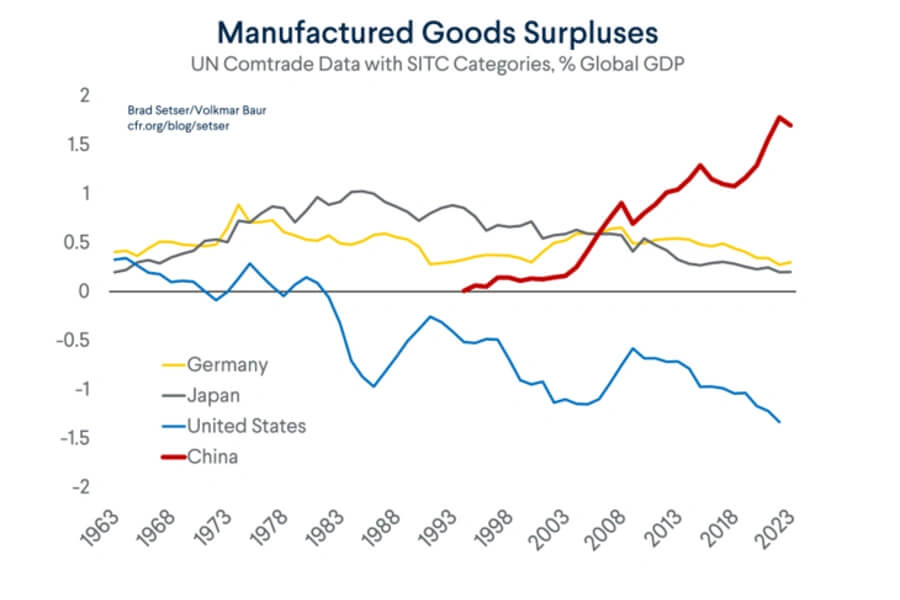

The scale of China’s manufacturing surpluses is hard to fathom—it amounts to about 2% of world GDP. That’s world GDP!

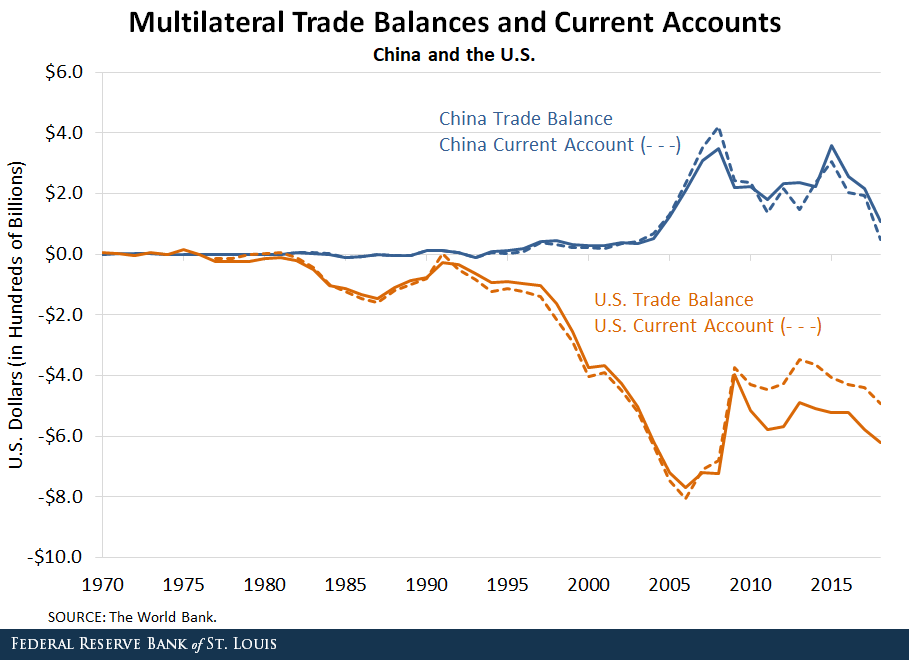

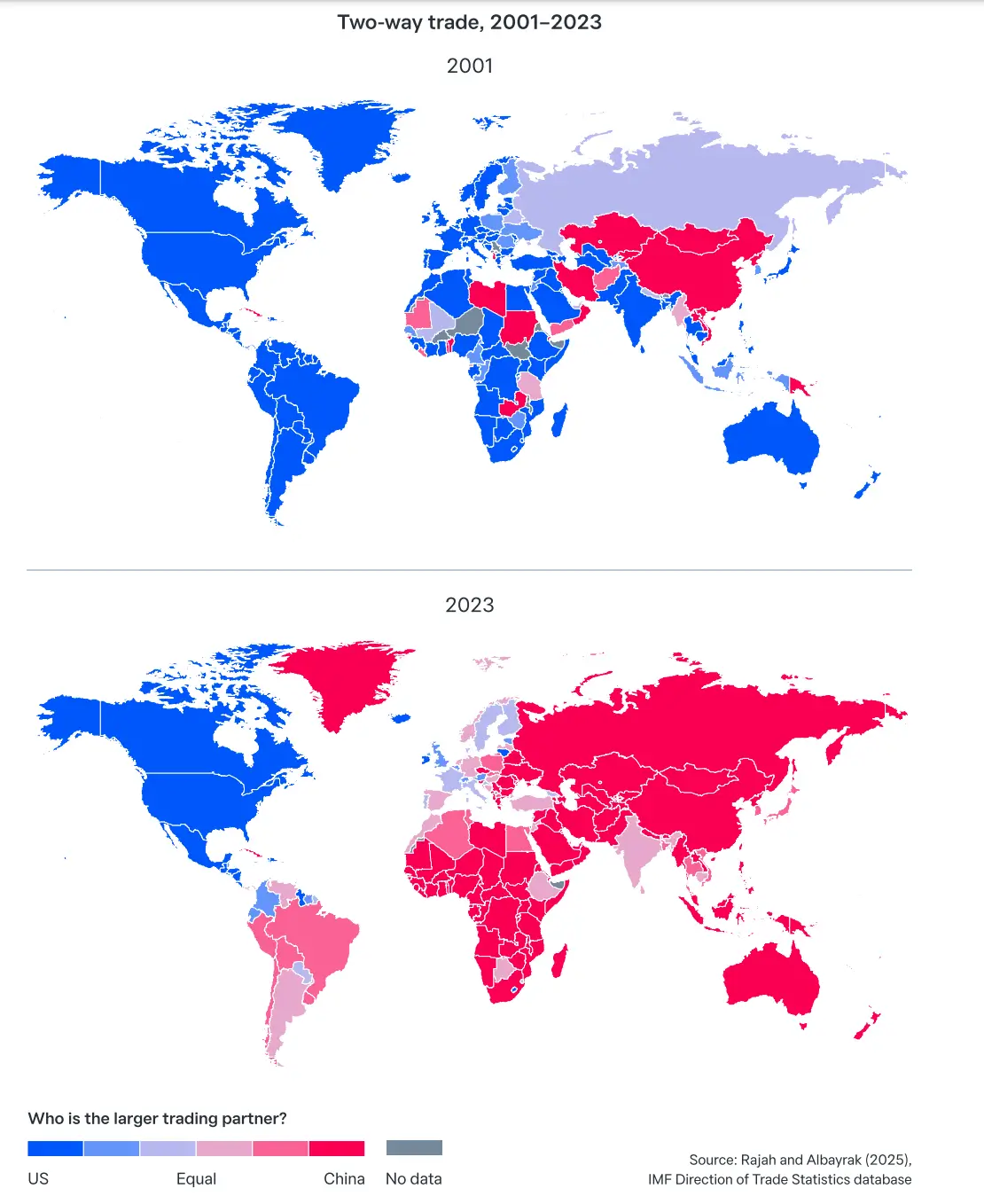

Another stat that always blows my mind is the number of economies for which China is the largest trading partner. In 2001, 80% of economies traded more with America than with China. By 2023, China had become the largest trading partner for over 70% of economies around the world.

These stats provide a quick, rough sense of the scale of China. In my view, there is the global economy—and then there is China.

Why Am I Saying All This?

When I started learning more about China, most of the sources I encountered offered shallow and incomplete takes on what was happening there. In reading and listening to these generic narratives, it’s easy to feel like you truly understand China, but nothing could be further from the truth.

China is not a country that lends itself to easy descriptions or comprehension. To give you a simple example, consider the question: how is the Chinese economy doing?

Well, if you look at traditional growth drivers—such as real estate, construction, and old-school heavy industries like steel, aluminum, chemicals, and entry-level manufacturing—that powered much of China’s growth since the 1990s, you’ll notice these sectors are now struggling. China willingly deflated its construction bubble and now appears to be grappling with overcapacity in areas like steel, aluminum, and chemicals as it moves away from these old economic growth drivers.

However, when you examine new-age industries—such as solar, wind, electric vehicles, artificial intelligence, and semiconductors—China is excelling. In fact, China has become so competitive in these areas that it poses a significant threat to large Western companies. Granted, these new industries are nowhere near replacing the traditional sectors, but one must realize that they have only emerged since around 2014 and are barely a decade old.

So, how does one answer the question: how is the Chinese economy doing—good or bad?

As Yuen Yuen Ang, Professor of Political Economy at Johns Hopkins University, wrote in a brilliant post:

So, is China in decline? The answer is both yes and no. While GDP growth is slowing, China is moving toward a green, high-tech economy, and it remains the world’s second-largest consumer market.

But as the country faces strong economic headwinds and consumers tighten their belts, investors must adapt to a new reality, and trade partners must diversify risks.

Still, predictions of the Chinese economy’s imminent collapse are overblown. If history is any guide, the only development that could truly destabilize the regime is a power vacuum at the top.

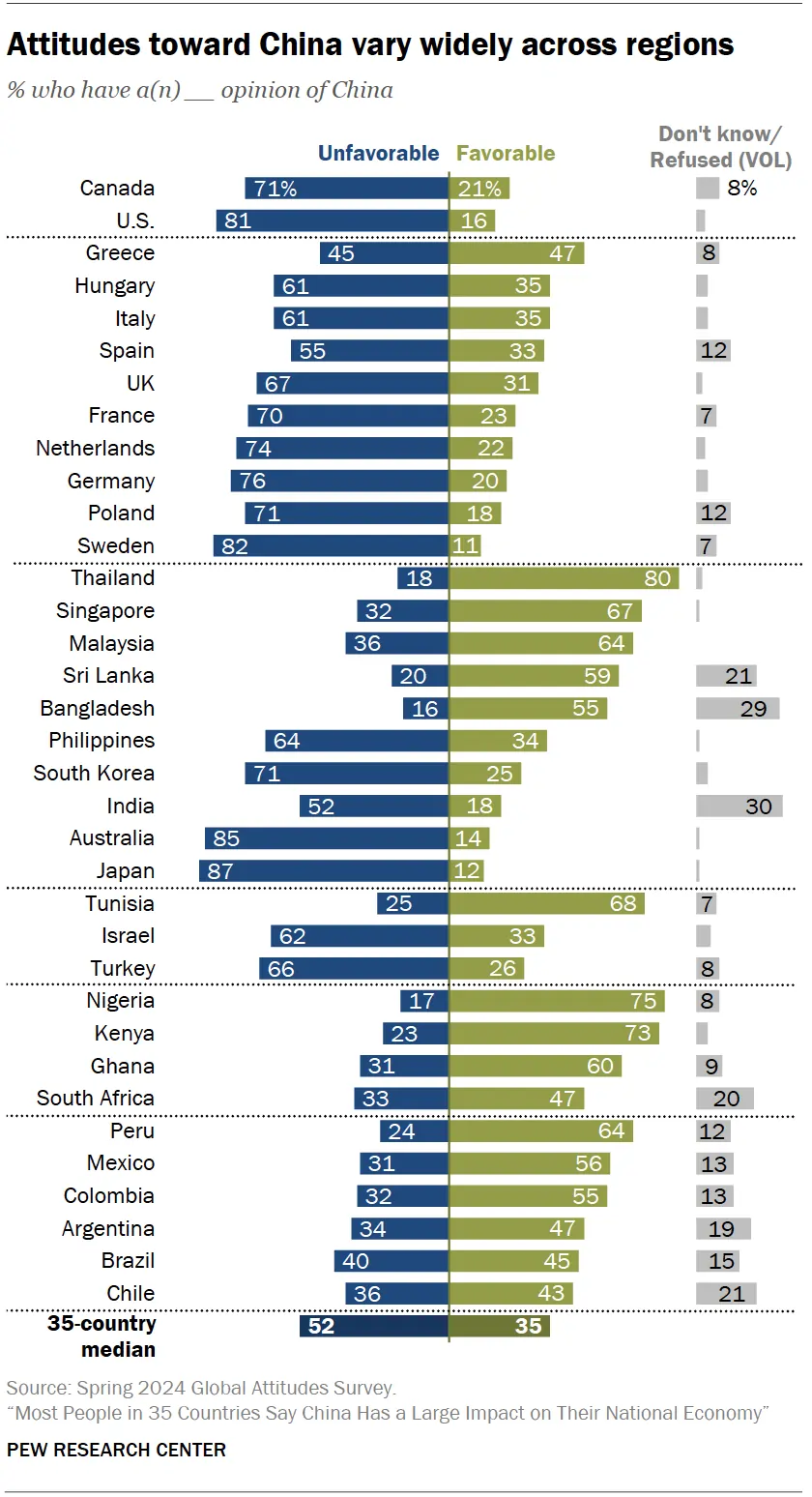

Another reason I’m fascinated by China is the stark contrast in how it is perceived. Depending on whom you ask, China is either a valuable partner or, as some might say, akin to Voldemort. In the West, China quickly transitioned from being seen as a developmental miracle to being viewed as the defining threat of the 21st century in less than a decade.

Historian Niall Ferguson described China in a recent interview:

"In many ways that was the interwar period—the period between Cold War I, when the Soviet Union was the major threat, and Cold War II, when China is the major threat. And you can't expect to carry on playing the game that you've played when China is not only a major trading partner, a major destination for Australian exports, but is also the principal threat to your national security."

This is not an isolated comment by a random historian; rather, it reflects the broader sentiment toward China prevalent in much of the West. In fact, despite deep divisions and partisanship in the U.S., both Democrats and Republicans agree that China must be contained. You can see this in the fact that Joe Biden not only maintained the tariffs imposed by Trump during his first term but also ratcheted them up dramatically.

Similar anti-China sentiment is evident in Europe, Australia, and many developing countries. However, the antipathy toward China is most intense in America—and it tends to be less pronounced elsewhere, largely because of trade. China is a huge trading partner for many Europeans, especially the Germans.

Interestingly, younger people tend to have favorable views on China.

The person who best captures and contextualizes this outright hostility toward China is historian Adam Tooze. Here’s a lightly edited transcript from a 2022 interview:

Adam Tooze: It must be said that, given the economic shocks China has suffered over the last couple of years—along with the serious impasse it faces in its real estate market and the huge accumulation of private-sector debt—predictions of China’s imminent overtaking of the United States seem less relevant. Instead, what matters is coming to terms with China’s existing weight in the world.

Rather than deferring this conversation to a symbolic moment when China’s GDP surpasses that of the United States, we should recognize that China’s current level of development, its technological presence, and its dominance in raw materials and energy markets already make it a key force globally.

We are effectively in a multipolar world. And it seems America cannot easily live with this reconfiguration of the global structure. You can see this not just in trade diplomacy, but in the “tech wars.” In 2020, the United States declared economic war on China by effectively launching a surgical strike against Huawei. Huawei was not just a cellphone manufacturer; it was the world’s fourth-largest private investor in R&D. America’s state machinery mobilized to eliminate it.

Essentially, the United States has announced it sees a hard limit on China’s technological development—right now, not in the future. It does not want China to progress rapidly in sophisticated AI or to become a global player in communications.

Menaka Doshi: Things do not always go as America wants it to.

Adam Tooze: They absolutely don't. But the question, of course, is what price China will pay to overcome that hostility and resistance.

Menaka Doshi: And you don't think China will pay a price—or is willing to pay a large one—to overcome it?

Adam Tooze: The real question is: what price will be paid, and by whom? China is already paying a price to overcome such hostility. The question is how high that price will be. If there is one thing the Chinese regime is committed to, it is sovereignty, and it seems determined to break through this obstacle.

Whatever one may think of China’s broader ideology, it is primarily a sovereignty project—a push to overcome the “century of humiliation.” That defines the entire project. So, to be told by the United States, “This far and no further in tech,” is, in effect, a declaration of war. It is basically an attempt to constrain China’s technological advancement, rather than a matter of seizing territory in the traditional sense.

Regardless of what one may think about its broader ideology, it is fundamentally a sovereignty project. It's about overcoming centuries of humiliation—that's the core of the whole endeavor. So, when the United States says, "this far and no further" in technology, it feels like a declaration of war. If America really wanted to choose a way to constrain China, it wouldn’t be about seizing territory.

Combined with what Niall Ferguson and others are saying, this open antagonism toward China is scaring the shit out of me. I don’t know enough history to conclude that such perceptions are normal when a new power rises to threaten an incumbent superpower. The only historical parallel I can think of is the rise of Germany—which ultimately led to WWI.

But the issue extends beyond public intellectuals making unhelpful comments. There is a palpable sense of paranoia among the Western economic and security establishments. This paranoia has led to a marriage of convenience between economic priorities and national security imperatives and has all but ended the "rules-based international order," if there ever was one.

That isn’t to say that China is an angel and the West is the devil—or vice versa. I think framing issues in terms of good and bad, or black and white, is profoundly unhelpful when grappling with such a complex topic.

Our understanding of this moment—where a new rising power is jostling for influence while the old superpower tries to thwart its ambitions—must be situated within both historical context and the contingencies of the present. Thinking in terms of “us vs. them” only repeats the mistakes that have haunted history.

It is imperative that we all try to learn history, understand the present context, and think rationally about what is happening. The competition between China and the U.S.—if it is indeed a competition—is the defining clash of our times. It’s important to develop useful frameworks and questions to help us understand this battle of worldviews.

I’ll end this post here. In upcoming posts, I’ll share what I am learning about the Chinese economy. My hope is that you begin to think critically about your preconceived notions and resist lazy, wishful thinking.